This full article ran on

poz.com on April 19, 2013

by Naina Khanna

I have been sitting with and following the reactions to Tyler Perry’s

Temptation over the last couple weeks. Within the HIV community, and outside of it. Within the feminist community, and in other communities of women. In communities of color, among reproductive justice folks, and outside of those spaces.

What has been most distressing to me is the way that Tyler Perry played on and abused the high levels of internalized stigma and oppression, evident in responses from women of color and women living with HIV with respect to the film. [In the movie, the character of Judith cheats on her husband and she contracts HIV from the other man.]

“She chose to leave Bryce.” “She made a choice to put herself at risk.” “She wasn’t grateful enough for what she had, so she deserved it.” “Harley is a monster, like the monster who infected me.” These are only a smattering of the comments I’ve seen, read, and heard over the last weeks.

My reaction to witnessing the dialogue among HIV-positive women is the same motivation that originally drove a group of 28 women to co-found Positive Women’s Network-USA in 2008, rejecting the seemingly widespread notion that women living with HIV were forever destined to be held up as examples and nothing more.

That our place in the HIV workforce, public health community and education efforts was relegated to storytellers regaling classrooms, legislative chambers, and church congregations with tales of our supposed guilt, sins, and transgressions, and, sometimes worse, of our supposed innocence.

Worse, women living with HIV seemed to largely accept our place in that structure. We are incentivized to be complicit in it for a $25 or $50 stipend every World AIDS Day and the occasional Sunday. How do you resist a paradigm when living on a fixed income and feeding your family—and even making sense of your own reality—may depend on your willingness to participate in it?

Watching

Temptation was triggering to me, as a woman of color living with HIV, because it preys on the worst fears and internalized self-loathing of people who are most likely to be living with HIV. Tyler Perry’s

Temptation teaches that:

1. I’m a woman, so I don’t know if or when I want sex. If I say no, I don’t mean it, and when I say no, it’s because I am trying to live up to a societal expectation that women should say no, even if we don’t mean it. Therefore a man has the right to interpret my “no” and to rape me based on his decision that I did not really mean “NO!”

2. Men with HIV are sexually irresponsible, predatory and violent, and fail to disclose.

3. As a woman, I should be so afraid of the big bad world that I should not dare consider leaving my relationship. (Also, it’s a slippery slope from teetotaler to using cocaine regularly.)

4. People living with HIV cannot even hope for loving relationships, let alone have them, no matter how long they live with HIV. Romance, sex, love, and children? Off the table entirely.

This final (and archaic) portrayal might be the one that most directly and thoroughly assaults the self-worth of women living with HIV. Patriarchy, family structures, and cultural codes teach us from an early age that women without partners and without children hold little stature in family and society, especially in communities of color.

Most women living with HIV in the United States are women of color and poor women, who already live at the intersection of multiple oppressions before their HIV diagnosis.

Thus, for a woman testing positive for HIV, or who suspects she may be HIV positive, motherhood and/or becoming a spouse or partner may be the only socially valued identity available to her.

If Tyler Perry’s portrayal is real, and we are sinful, secretive monsters, unworthy of love and incapable of reproduction, what is the incentive for any woman to learn that she is HIV-positive and for any person living with HIV to disclose her/his status?

Research and data discredit every one of Perry’s points about people living with HIV, not to mention the assumptions about who may be at risk for HIV. Studies show that the overwhelming majority of people living with HIV

practice safer sex once they know their HIV status. HIV-positive people date, and more often than not, seem to disclose, and many are in long-term relationships with HIV-negative or positive partners and spouses. Oh, and by the way—

yes, we can have children! (Hello, 1990s.)

However, the majority of folks who encounter people living with HIV may not know this information, and certainly the majority of folks testing positive for HIV do not initially have complete information, and thus Perry’s portrayal is dangerous, deceptive and misleading. Perpetuating HIV stigma creates obvious problems in expanding HIV testing and ensuring that people living with HIV are in medical care and are safe disclosing to their partners.

But most of Perry’s messages have already been largely internalized by women living with HIV, as evidenced in the troubling response among many HIV-positive women to

Temptation.

It’s just not that simple. Let me say it: It sucks to be cheated on or lied to. And sometimes people do irresponsible things, stupid things, hurtful things. Sometimes they thought about it beforehand and sometimes they didn’t. It is irrelevant. HIV is not punishment for sins, bad behavior, insensitivity, irresponsibility, or naiveté. Lots of people do shitty things and do not get HIV. That is also irrelevant.

HIV is not something that “guilty” people get. It is not a punishment for cheating, lying, using drugs or alcohol, having more than one partner, not asking the right question, or not appreciating a partner enough.

HIV is also not something that people “innocently” get. HIV is a disease transmitted by four bodily fluids. Nobody “deserves” HIV or “doesn’t deserve” HIV, just like nobody deserves or does not deserve cancer. And most of us didn’t get HIV by having sex with the devil.

Also, love, eternal happiness, husbands and children are not shiny little prizes you win by being faithful or having sex only with the lights off.

Temptation is sleazy, trashy entertainment designed to profit by preying on our collective worst fears.

Innocence implies that guilt is possible, and guilt implies that innocence is possible. One is meaningless without the other. Allowing ourselves, as people living with HIV, to fall into any such dichotomy perpetuates the story that there are people who “deserve” a disease and its consequences—and worse, that it is permissible to hold any one of us up as an example to moralize. It’s just not that simple. Let’s not let Tyler Perry convince us it is.

But, there are conditions that put people at increased risk for poor health, and those are things we can and should work to change.

We ought to be angry with the laws, policies and norms that make it acceptable for companies to dump toxic waste in poor communities, increasing cancer rates.

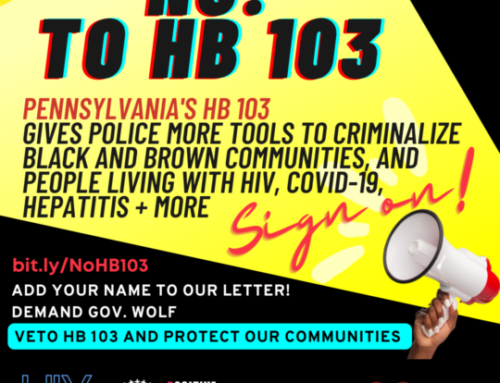

We ought to be furious with the HIV criminalization laws, policies and social norms that make it challenging, even dangerous, to disclose one’s HIV status. A bill passed in Kansas last month expanded authority of state and local health officials

to quarantine people living with HIV. Larry Dunn’s false beliefs about HIV led him

to brutally murder his girlfriend after she disclosed her status. A man in Peru allegedly set fire

to his HIV-positive gay son earlier this week. And over 32 states in the United States have laws criminalizing people with HIV at this time.

Countless people living with HIV and advocates throughout the nation are working to change these laws, bills, and stigmatizing beliefs. Among them, the

Sero Project and the

Positive Justice Project have advocated tirelessly to repeal laws and change policies that criminalize and stigmatize people living with HIV in the United States. The

Positive Women’s Network-USA has a treasure trove of resources produced by HIV-positive women framing a policy and communications dialogue that uplifts human rights and dignity.

Tyler Perry, on the other hand, exemplifies an irresponsible mouthpiece that preys on the fears, myths, misperceptions, and misguided policies we seek to reverse. Media has the power to change how we feel about ourselves and each other. Perry’s messages keep people living with HIV closeted, fearful, and isolated. They kill us.

It is this fear of ourselves and what we represent that is depressing, that makes us slowly lose the will to live, to fight, to leave unhealthy or dangerous relationships, to take our medication, to get to the doctor one more time.

It is our own worst fear that Tyler Perry’s portrayal of us—a story told over and over—is real, and that the best we have to hope for is a sexy, sweet, remarried ex who will ask us about our T-cell count.

And just maybe, the messages portrayed by Tyler Perry are the reason why many women living with HIV in the United States are not in regular medical care.

It takes a very, very long time to undo decades of media and public health officials and faith based institutions telling us that people living with HIV are getting what we deserve. It takes even longer to undo the internalized oppression that comes from colonization and slavery and displacement. And I cannot imagine how long it will take women to undo internalized sexism and its deadly consequences.

For the estimated 300,000 women living with HIV in the United States, Tyler Perry’s

Temptation preys on the worst of all that. For this, I charge him with at least 300,000 counts of self-doubt and recrimination, a million moments of fear and hopelessness, hundreds of failures to disclose, countless refused HIV tests, thousands of missed medical appointments, suicides, homicides, and setting us back in our HIV response for over than a decade.

Tyler Perry must commit to doing better. Call

PWN-USA and the U.S. People Living with HIV Caucus before you make your next movie on HIV. Otherwise, someone, please take away that camera.

I have been sitting with and following the reactions to Tyler Perry’s Temptation over the last couple weeks. Within the HIV community, and outside of it. Within the feminist community, and in other communities of women. In communities of color, among reproductive justice folks, and outside of those spaces.

What has been most distressing to me is the way that Tyler Perry played on and abused the high levels of internalized stigma and oppression, evident in responses from women of color and women living with HIV with respect to the film. [In the movie, the character of Judith cheats on her husband and she contracts HIV from the other man.]

“She chose to leave Bryce.” “She made a choice to put herself at risk.” “She wasn’t grateful enough for what she had, so she deserved it.” “Harley is a monster, like the monster who infected me.” These are only a smattering of the comments I’ve seen, read, and heard over the last weeks.

My reaction to witnessing the dialogue among HIV-positive women is the same motivation that originally drove a group of 28 women to co-found Positive Women’s Network-USA in 2008, rejecting the seemingly widespread notion that women living with HIV were forever destined to be held up as examples and nothing more.

That our place in the HIV workforce, public health community and education efforts was relegated to storytellers regaling classrooms, legislative chambers, and church congregations with tales of our supposed guilt, sins, and transgressions, and, sometimes worse, of our supposed innocence.

Worse, women living with HIV seemed to largely accept our place in that structure. We are incentivized to be complicit in it for a $25 or $50 stipend every World AIDS Day and the occasional Sunday. How do you resist a paradigm when living on a fixed income and feeding your family—and even making sense of your own reality—may depend on your willingness to participate in it?

Watching Temptation was triggering to me, as a woman of color living with HIV, because it preys on the worst fears and internalized self-loathing of people who are most likely to be living with HIV. Tyler Perry’s Temptation teaches that:

I have been sitting with and following the reactions to Tyler Perry’s Temptation over the last couple weeks. Within the HIV community, and outside of it. Within the feminist community, and in other communities of women. In communities of color, among reproductive justice folks, and outside of those spaces.

What has been most distressing to me is the way that Tyler Perry played on and abused the high levels of internalized stigma and oppression, evident in responses from women of color and women living with HIV with respect to the film. [In the movie, the character of Judith cheats on her husband and she contracts HIV from the other man.]

“She chose to leave Bryce.” “She made a choice to put herself at risk.” “She wasn’t grateful enough for what she had, so she deserved it.” “Harley is a monster, like the monster who infected me.” These are only a smattering of the comments I’ve seen, read, and heard over the last weeks.

My reaction to witnessing the dialogue among HIV-positive women is the same motivation that originally drove a group of 28 women to co-found Positive Women’s Network-USA in 2008, rejecting the seemingly widespread notion that women living with HIV were forever destined to be held up as examples and nothing more.

That our place in the HIV workforce, public health community and education efforts was relegated to storytellers regaling classrooms, legislative chambers, and church congregations with tales of our supposed guilt, sins, and transgressions, and, sometimes worse, of our supposed innocence.

Worse, women living with HIV seemed to largely accept our place in that structure. We are incentivized to be complicit in it for a $25 or $50 stipend every World AIDS Day and the occasional Sunday. How do you resist a paradigm when living on a fixed income and feeding your family—and even making sense of your own reality—may depend on your willingness to participate in it?

Watching Temptation was triggering to me, as a woman of color living with HIV, because it preys on the worst fears and internalized self-loathing of people who are most likely to be living with HIV. Tyler Perry’s Temptation teaches that: