State Violence Won’t End Interpersonal Violence. What Will?

by Kelly Flannery, PWN If/When/How Reproductive Justice HIV Legal Fellow

May 23, 2019: Over 60% of women living with HIV in the U.S. have experienced intimate partner violence at some point in their lives. An epidemic of violence against people of transgender experience, particularly trans women of color, confronts us with each new headline about vicious attacks and brutal murders. These statistics, headlines, and personal experiences are what often comes to mind when thinking about violence against women. Yet interpersonal violence is only part of the story. Some of the “solutions” our society favors to address such violence–such as law enforcement and the courts–fail to provide safety for the survivors and victims, and can actually lead to more violence in our communities and against us as individual survivors.

At Positive Women’s Network – USA (PWN), we recognize and organize to end interpersonal, community, and structural violence against women and people of trans experience. These are harms that originate from people we interact with, within our community, and from state and social institutions.

“Carceral feminism” is a term coined by Elizabeth Bernstein in 2007. It describes an approach to addressing violence against women that relies on policing, prosecution, punishment, and incarceration. The idea of carceral feminism is straightforward: to end violence against women, we should lock up the people who are perpetrating violence. In reality, this approach is overly simplistic and destructive.

The criminal legal system itself perpetuates violence disproportionately against marginalized communities. According to statistics from 2017, police killed 1,147 people in one year, 92% through police shootings. Most began in response to a suspected non-violent offense, and only 1% of the officers involved were charged with a crime. Black people were more likely to be killed by police, more likely to be unarmed, and less likely to be threatening someone when killed. These numbers do not include other forms of police violence, like surveillance, harassment, and non-fatal beatings and injuries tragically common in Black, Latinx, immigrant, and trans communities.

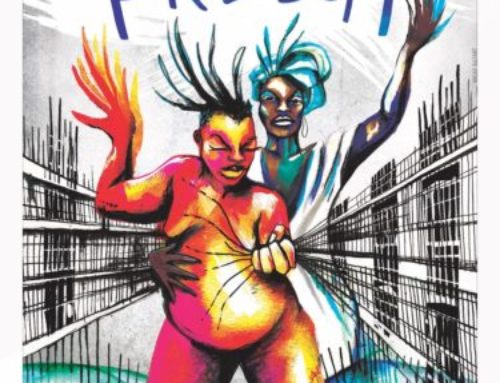

Prisons, jails, and detention centers are always a site of state violence. The number of women in local, state and federal prisons and jails has dramatically increased over the last several decades. More than eight times as many women are incarcerated today as in 1980. Furthermore, the vast majority of women in prison have experienced violence themselves. According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), 79% of women in federal and state prisons reported physical abuse and as many as 90% of the women in prison for killing men had previously been battered by those men.

Black, Latinx, immigrant, and LGBTQ communities are disproportionately targeted and harmed by the criminal legal system before, during, and after incarceration. This results in even worse economic, educational and health inequities. Instead of ending violence against women, the carceral feminist approach actually relies on and exacerbates violence against those most vulnerable to it.

Women and trans people experiencing violence need a hand up, not handcuffs

Rather than relying on punishment and prison, ending violence against women and people of trans experience living with HIV requires addressing the underlying economic insecurity and structural inequities that create the conditions for gender-based and interpersonal violence. It requires drastic changes in how we look at and respond to both violence and human need, but it can be accomplished. We demand the conditions that make our collective liberation possible: access to affordable health care, good jobs, and affordable housing; and ending criminalization and the prison system.

Rather than relying on punishment and prison, ending violence against women and people of trans experience living with HIV requires addressing the underlying economic insecurity and structural inequities that create the conditions for gender-based and interpersonal violence. It requires drastic changes in how we look at and respond to both violence and human need, but it can be accomplished. We demand the conditions that make our collective liberation possible: access to affordable health care, good jobs, and affordable housing; and ending criminalization and the prison system.

To be clear, survivors reaching out for support and protection–even to the police–are not the problem. The problem is our social, economic, and political reliance on carceral solutions, especially when the criminal legal system in the U.S. tends to perpetuate and deepen trauma. Carceral feminism drowns out the possibility of social justice and dignity-oriented solutions to violence.

Women and trans people experiencing violence need a hand up, not handcuffs. By creating systems that support the health and well-being of all, we can tackle the structural underpinnings that stop many from escaping dangerous, violent situations in the first place.

When violence does occur, there are non-carceral alternatives that prioritize healing trauma, rebuilding community, and changing unjust systems.

- Restorative justice promotes reconciling community members, survivors, and those who have committed crimes through accountability and shared values.

- Transformative justice recognizes how unjust social systems and institutions relate to violence and creates an obligation to transform (or abolish) them for the better.

The transformative and restorative approaches both reject the punitive, retributive practices on which the prison industrial complex relies, but transformative justice goes further. It requires us to address the conflict between survivor, offender, and community and the social issues, such as poverty, and governmental action or inaction that have led to, allowed, or escalated the conflict.

The U.S. criminal legal system is a failed experiment. Restorative and transformative justice offer better answers.

The U.S. locks up more people than any other country in the world: We have only 4.4% of the world’s population but 22% of the world’s prisoners. Though only 5% of the world’s female population lives in the U.S., we account for nearly 30% of the world’s incarcerated women. (And this statistic does not account for women of trans experience, who are often held in male prisons in the U.S.!)

Laws in the U.S. are enforced unequally. Police target low-income and marginalized communities — the same communities that suffer under the carceral feminist approach to ending violence against women. People from these same communities are more likely to be put in and stay in jails and prisons following arrest: Unable to afford bail, they wait in jail for court dates before they have been convicted; Unable to afford expensive private lawyers and facing deeply entrenched racism in the courts, they are more likely to be convicted and to face longer sentences.

Criminal laws that intend to address violence against women actually perpetuate it. Survivors themselves are often even punished for reaching out for help. At least 25 states have mandatory arrest laws that require police to arrest someone in domestic violence cases. Many others leave it to the officer’s discretion whether one or both people involved should be taken into custody. Such policies put those who are viewed as “aggressive” or do not typically fit the “victim” stereotype — like people who are Black, Latinx, queer, non-English speaking, or trans — at risk of arrest for reporting violence against them.

Across the U.S., towns and cities are adopting chronic nuisance ordinances that punish landlords if the police are called too often to a property, even if someone calls 911 because of concern for their safety. The intent is to reduce crime. In practice, the ordinances undermine public safety by encouraging landlords to evict or refuse to rent to perceived “problem tenants” and punishing people for asking for help. These ordinances only exacerbate the structural power imbalances, economic insecurity, and lack of stable housing that often result in survivors staying in abusive relationships.

On the positive side, restorative justice approaches to violence and harm have expanded in the U.S.:

- 38 states incorporate restorative justice principles, like survivor and community involvement in the justice process, in their law to some extent.

- 20 states specifically include restorative practices like mediation between the survivor and the person convicted of a crime.

- Six states and many local school districts encourage positive interventions and restorative responses over school discipline.

However, courts and prosecutors do not apply these laws equally or consistently. They also depend on the victims understanding their choices and choosing restorative justice approaches over the more traditionally favored criminal legal system ones. This means we must do a better job of educating our communities and work toward changing the culture of our society that relies on police, courts, and prison to address violence.

The restorative justice approaches that exist in U.S. law today fall short of transformative justice. Without systemic change in the economic, criminal legal, health care, and immigration systems writ large, any restorative justice approach will fall short of ending violence.

PWN advocates for changing and improving systems that deliver health care, housing, and economic security, as well as ending criminalization.

You can learn more about our vision, our approach, and specific policy recommendations to end violence against women and people of trans experience living with HIV on our website here and in our webinar today (May 23, 2019) at 3pm EDT/12pm PDT.

| Register here |